If you’re reading this newsletter, odds are that you, like me, grew up watching nature documentaries, dreaming about roaming the African savannah or bushwhacking trails in the Amazon rainforest to track down exquisite plant life, outlandish insects, and species of animals new to science. Good news! If you’re still looking for a safari, you don’t need a pith helmet—just a smartphone.

Nowadays, lots of apps exist to tell you what you’re looking at when you’re on the trail, but one of these leads the pack: iNaturalist, which was first conceived as a master’s project by students at UC–Berkeley in 2008. Since then, it has grown to include 4.3 million users worldwide who have contributed over 300 million observations, and that data has been harnessed in over 5,000 scientific publications.

Even in the most mundane suburban backyard, these observations can lead to thrilling discoveries. Just recently, researchers confirmed that a weevil spotted in eastern Pennsylvania by iNat user Neal Kelso was a greater chestnut weevil—a species thought to have been wiped out when chestnut blight decimated American chestnut trees. Evidently doing well on blight-resistant hybrid chestnuts, the weevil is making a comeback after two decades of obscurity, offering hope that the web of species that once depended on these trees can be reconstructed. The weevil is not alone; it’s one of nearly 500 species to have been rediscovered thanks to iNaturalist.

The Kindness of Strangers

One of the things that sets iNaturalist apart is that it’s not just an app; it’s a community. The machine learning–based “computer vision” (CV) that helps users identify the organisms they see is just the beginning. To reach Research Grade, the level at which an observation is shared with the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), it must have at least two agreeing IDs from the community (or a two-thirds majority if there are conflicting IDs). The CV isn’t perfect—it might mistake a beetle grub for a cicada nymph, for example—but the iNaturalist community includes many experts who volunteer their time to help curate and identify observations. Disagreement, which is often necessary to reach a correct ID, is inherent to this process, but in spite of that (or maybe because of it?), the iNaturalist community is so civil and supportive that a 2022 New York Times article dubbed it “The Nicest Place Online.”

How WWC Can Benefit

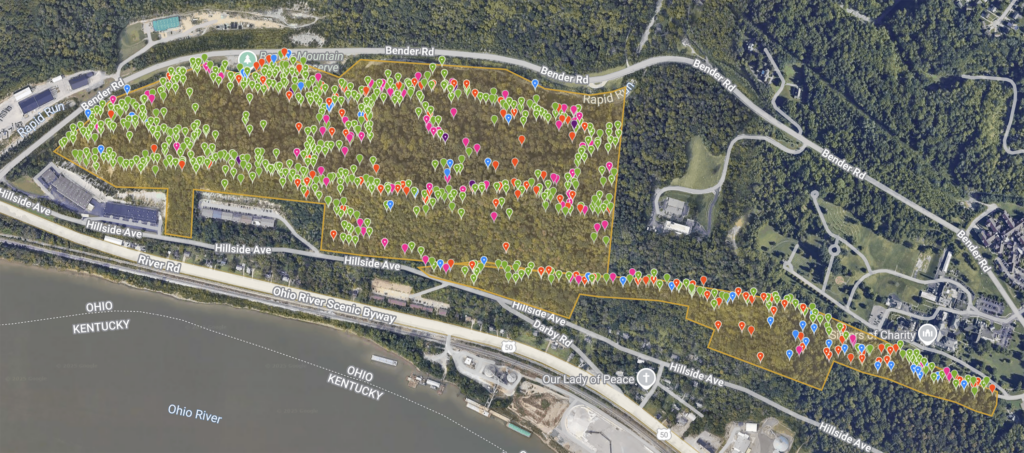

One of the first steps in conservation is assessing biodiversity. Put simply, you have to figure out what’s there before you can protect it, and establishing a baseline is essential so that any changes (like the decline or increase of species) can be detected. Our main iNaturalist project, Biodiversity of the Western Wildlife Corridor, is helping us keep track of the plants, animals, and other lifeforms in our preserves. Since its launch in late 2020, 231 different observers have turned up 771 species, with over 3,500 observations and new ones being added almost daily.

This summer, Sarah Kent and I added another project, Mothing at the Kirby Nature Center (July 2025), to track the insects and other critters that appeared during our mothing event. This bioblitz-style project was limited to that evening, but we will create an umbrella project for future mothing events, gathering all of our bioblitzes into an overview of WWC’s arthropod activity. Our main Biodiversity project automatically collects these records, too, contributing to an at-a-glance look at the species richness of our preserves.

Projects like these help connect us with our community to engage members in conservation efforts. They can help detect species we want to control (like spotted lanternfly) as well as species we want to protect. They can help us plan long-term monitoring strategies and make sustainable plans for land stewardship. Importantly, all of these facets can be great assets in writing grant proposals and applying for funding to keep WWC going strong.

Start an iNat Habit!

When I first joined iNaturalist in 2019, I found that it quickly became a way of life. Now, I rarely go for a hike without taking at least a hundred photos, and I enhance my fitness regimen with “photographer’s yoga” as I stretch to get just the right angle for a photo of the ID features of an insect or wildflower. I hope you’ll develop a similar habit, and that you’ll join our projects and contribute your own observations to help WWC better understand and care for our beautifully biodiverse preserves!

If you’re new to iNaturalist, there are three main ways to get started:

- Seek:the most basic app, geared for kids and casual users. You don’t even have to create an account for Seek, but you’ll need one if you want to save your observations and contribute to our projects.

- TheiNaturalist app, which now includes an easy way to follow notifications so you don’t miss out on social aspects. It’s the best way to use iNaturalist on a smartphone during your hikes.

- Through the web:on a bigger screen, iNaturalist’s web interface provides the most powerful array of search filters, a batch uploader (great if you use a non-phone camera), identification tools, and access to the iNaturalist Forum, where you can follow discussions on hot topics. The web interface comes with the highest learning curve, but it’s worth it!